15 Columns

Introduction

Click to expand

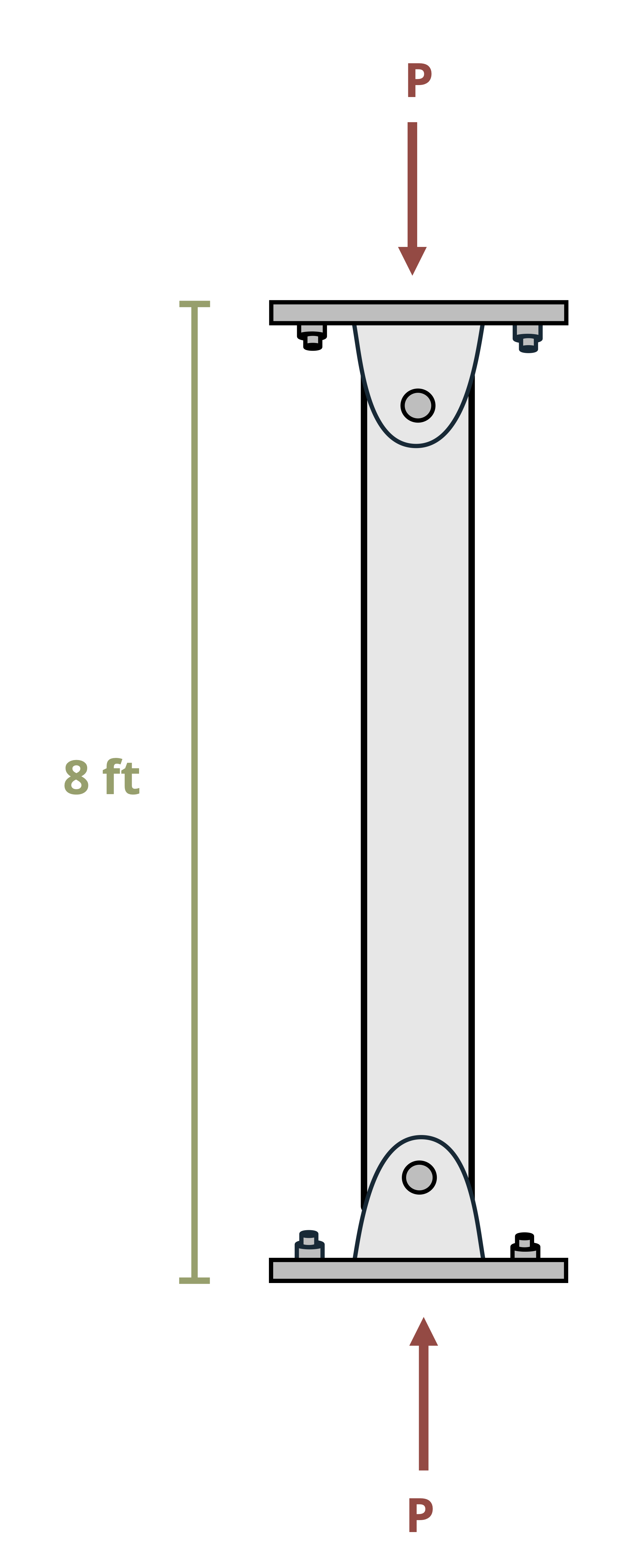

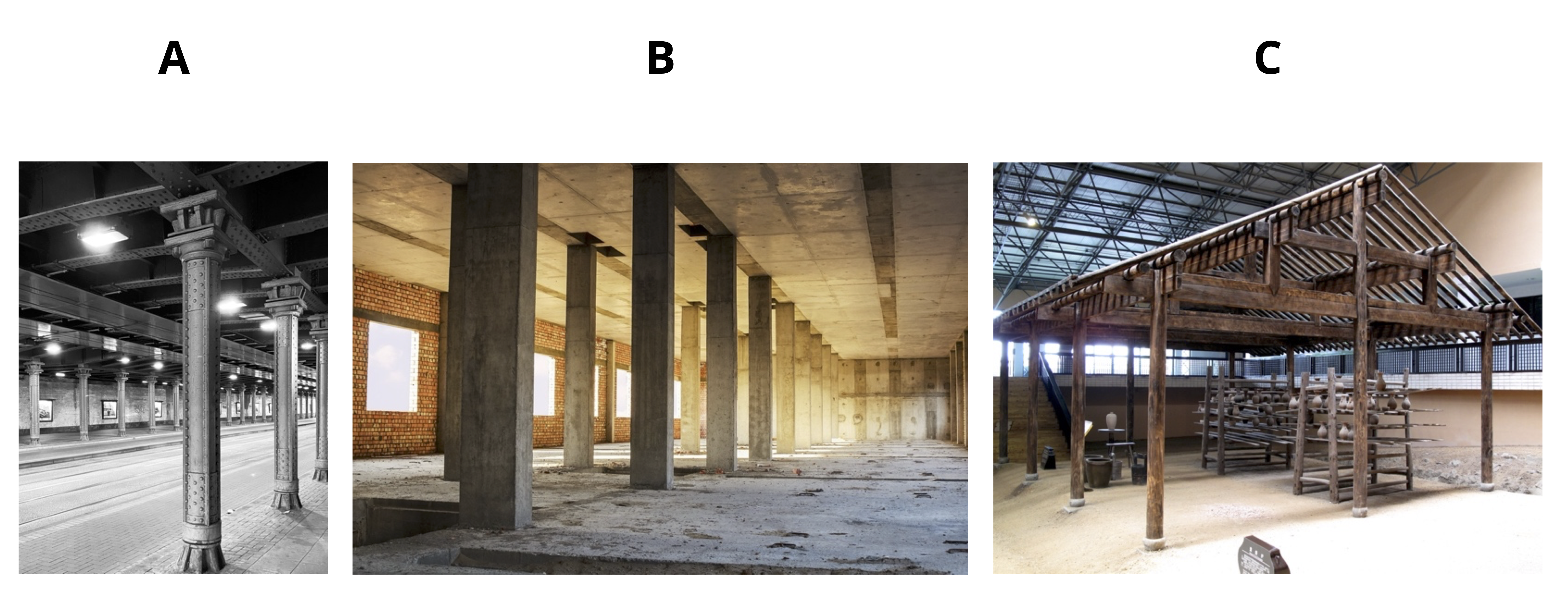

Until now, our focus has been primarily on meeting strength and deflection criteria. While these aspects are crucial, it’s equally important to ensure the structure’s stability. In this chapter, we will delve into the stability analysis of long and slender members subjected to compressive loading, commonly referred to as columns. Some examples are shown in Figure 15.1. When the compressive load reaches a critical point, columns may undergo sudden sideways deflection, a phenomenon known as buckling. After buckling, a column is unable to support any further load. This chapter will focus on long, slender, homogeneous, axial compression members, otherwise known as columns.

In Section 15.1 we’ll derive the buckling formula for columns that are supported by pin connections at both ends. In Section 15.2 we’ll extend this to consider other common end conditions.

15.1 Euler’s Formula for Buckling

Click to expand

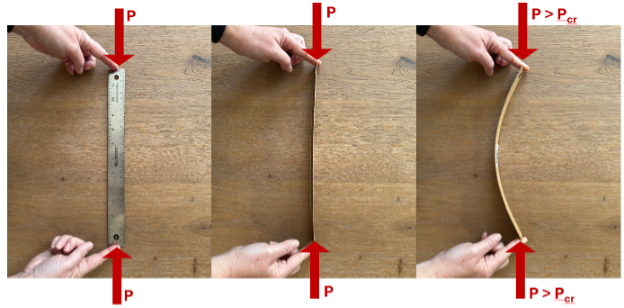

Even in ideal conditions, buckling often occurs for long slender members at loads significantly lower than the material’s crushing or compression limit. When a long slender object is subjected to axial loading, it may buckle once the load reaches a critical threshold known as the critical load, Pcr. At this point, the object experiences significant lateral deflection perpendicular to the load direction, so columns should be designed such that the applied load does not exceed the critical load.

Buckling of a ruler (long slender member) is depicted in Figure 15.2. The ruler in the left and center photos is subjected to axial load P that is less than the critical load, Pcr. This is known as stable equilibrium. In the photo on the right, the axial load, P, exceeded the critical load Pcr, causing a significant lateral deflection. This is known as unstable equilibrium.

15.1.1 Stability

We can consider stability by using a simplified model of a pinned-pinned column. This column will consist of two ridged bars connected with a pin and a spring with a stiffness k, as shown in Figure 15.3 (A). When the load, P, is small, the system remains vertical, and the spring is unstretched. If point C is displaced to the right a small amount, Δ, the spring will produce a force F = kΔ, as shown in Figure 15.3 (B). This force is used to resist the horizontal forces, Px = Ptanθ, as shown in Figure 15.3 (C).

Since θ is small:

\[ \sin \theta \sim \theta \text { and } \tan \theta \sim \theta \]

so

\[ \Delta=\theta \frac{L}{2} \text { and } 2 P_x=2 P \theta \]

Using the spring restoring force equation F=kΔ, then substituting in for Δ we have:

\[ F=k \theta \frac{L}{2} \]

If the spring restoring force is greater than the axial force, then we have a stable equilibrium.

\[ \begin{aligned} & F>P \\ & k \theta \frac{L}{2}>2 P \theta \end{aligned} \]

The θ cancels out, and we can solve for P:

\[ P<\frac{k L}{4} \]

Similarly we can solve for the expression for unstable equilibrium F < P:

\[ P>\frac{k L}{4} \]

The point at which F = P is crucial as it is the line between stable and unstable equilibrium. We call this the critical load Pcr:

\[ P_{c r}=\frac{k L}{4} \]

Thus, if the load P exceeds Pcr, then the system will be unstable, and if P is less than Pcr, then the system will be stable. We will use Pcr in the next section to determine the bucking load of columns.

15.1.2 Euler’s Formula

As mentioned in earlier sections, members can fail due to material yielding or fracturing. However, instability represents another critical failure mechanism that requires consideration. We will use Euler’s formula to calculate the theoretical buckling load. To do this, we will start with the simplest of columns, pinned-pinned end connections. This means that the column cannot translate but can rotate as shown in Figure 15.4.

Columns are similar to beams rotated 90 degrees, so we can use what we already know about the elastic curve.

\[ \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}=\frac{M}{E I} \]

We can use the free-body diagram in Figure 15.4 (C) to sum moments about any point on the lower column section.

\[ \begin{aligned} & \sum M=0=M+P y \\ & M=-P y \end{aligned} \]

We can now substitute this expression into the elastic curve equation:

\[ \begin{aligned} & \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}=\frac{-P y}{E I} \\ & \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}+\left(\frac{P}{E I}\right) y=0 \end{aligned} \]

This is a linear, homogeneous, second-order differential equation with constant coefficients, which has a general solution of:

\[ y=C_1 \sin \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} x\right)+C_2 \cos \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} x\right) \]

The two constants, C1 and C2, can be determined by imploring boundary conditions. Since y = 0 at x = 0 and y = 0 when x = L. The first condition gives:

\[ \begin{aligned} &0 =C_1(0)+C_2(1) \\ & C_2 =0 \end{aligned} \]

The second boundary condition, x = L when y = 0 results in:

\[ 0=C_1 \sin \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} x\right)+0 \]

The equation is satisfied if C1 = 0. However, this is a trivial solution that implies y = 0 and there is no lateral deflection. For the nontrivial solution, the sine function must be equal to zero, which requires:

\[ \begin{aligned} &\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} L=n \pi \\ & \text {where } n=1, 2, 3, 4,... \end{aligned} \]

The smallest value of P occurs when n = 1; substituting this and rearranging gives us Euler’s formula:

\[ \boxed{P_{c r}=\frac{\pi^2 E I}{L^2}} \tag{15.1}\]

where:

E = Elastic modulus of the material [Pa, psi]

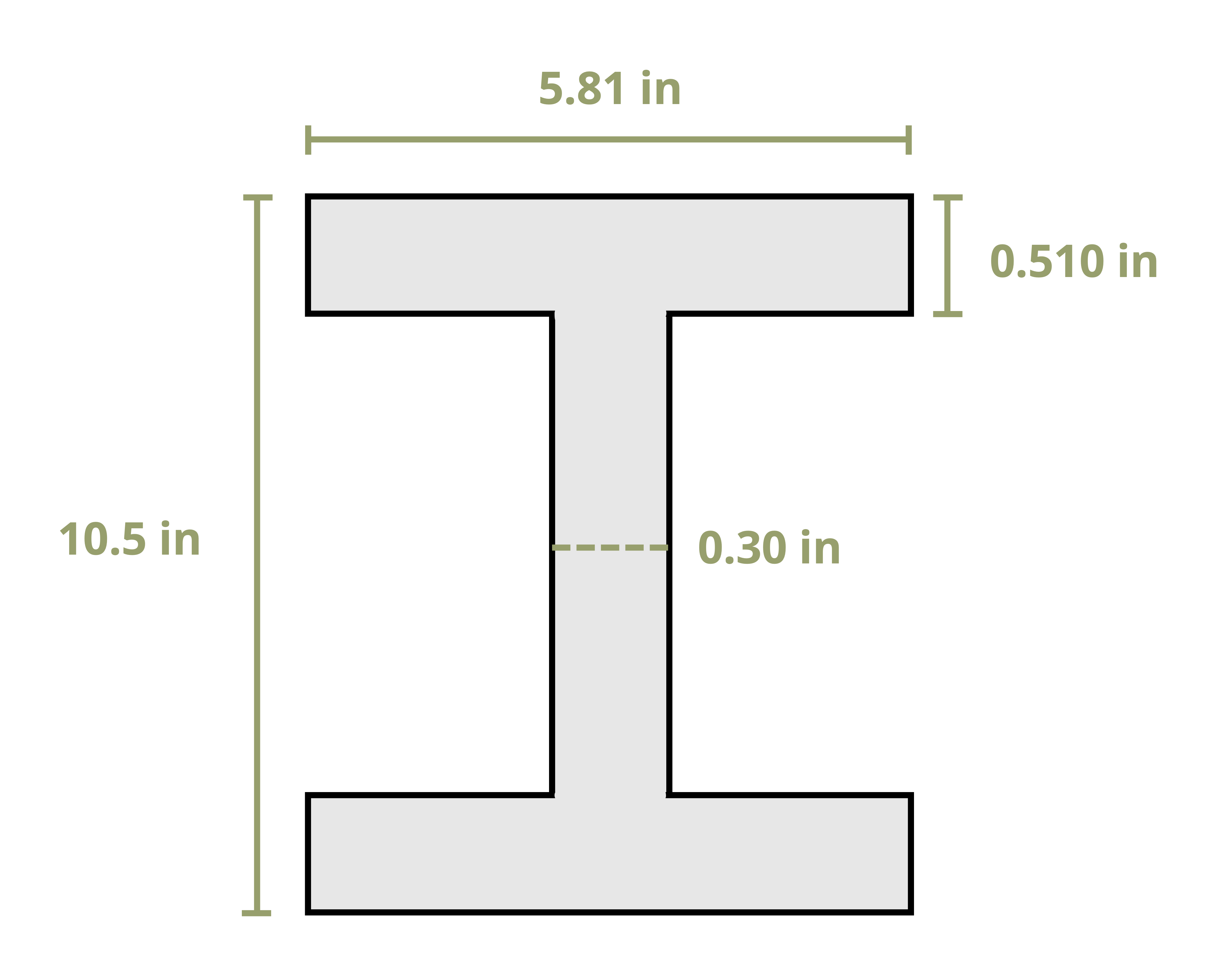

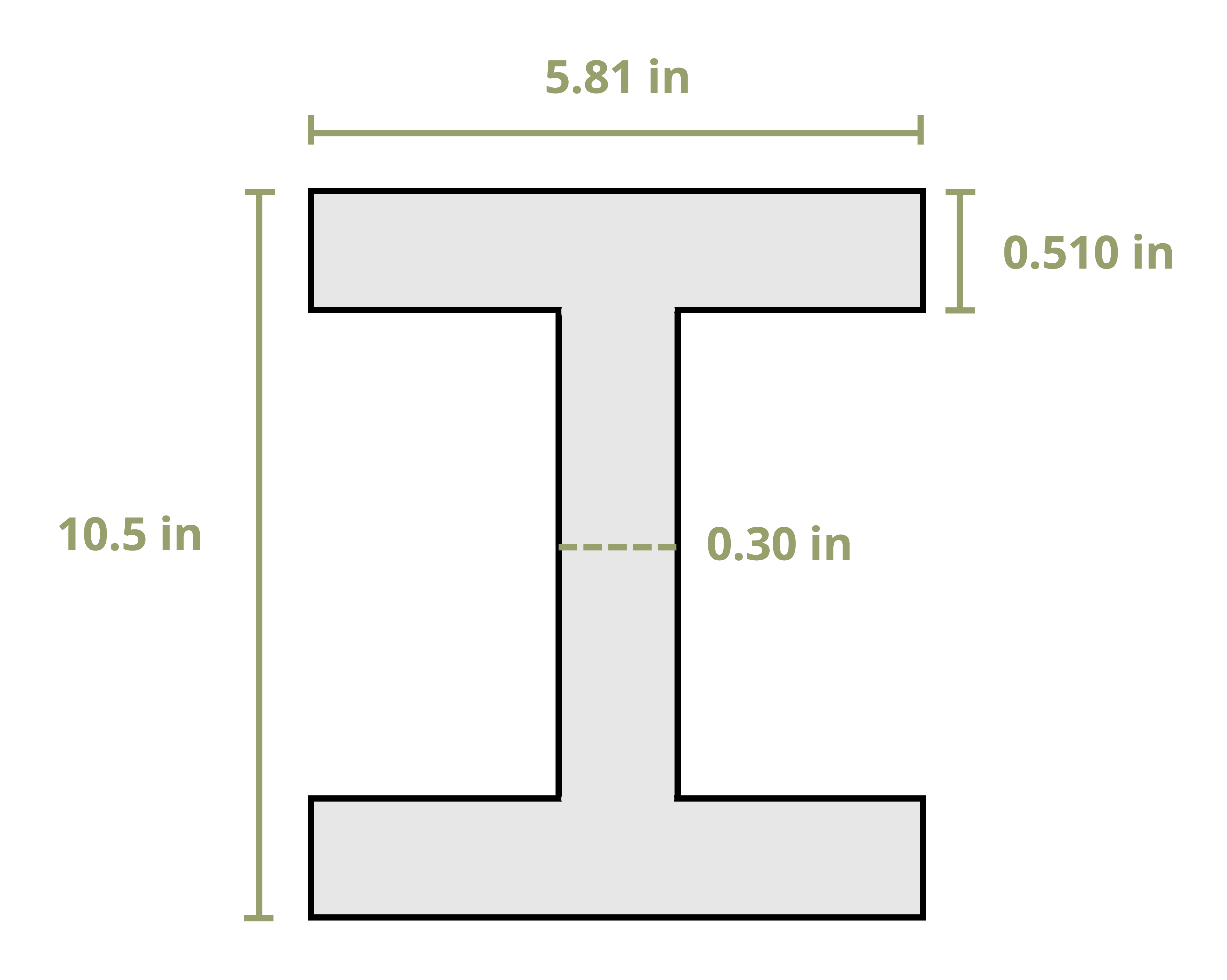

I = Area moment of inertia for the column [m4, in.4]. Note if Ix and Iy are different, use the smaller value.

L = Unsupported length of the column (pinned=pinned connection) [m, in.]

This is named after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler who developed this formula in 1744. Other bucking modes can exist (n = 2, n = 3, n = 4, etc.) but are less common as the load required for those higher modes would be much larger. The first three bucking loads can be seen in Figure 15.5.

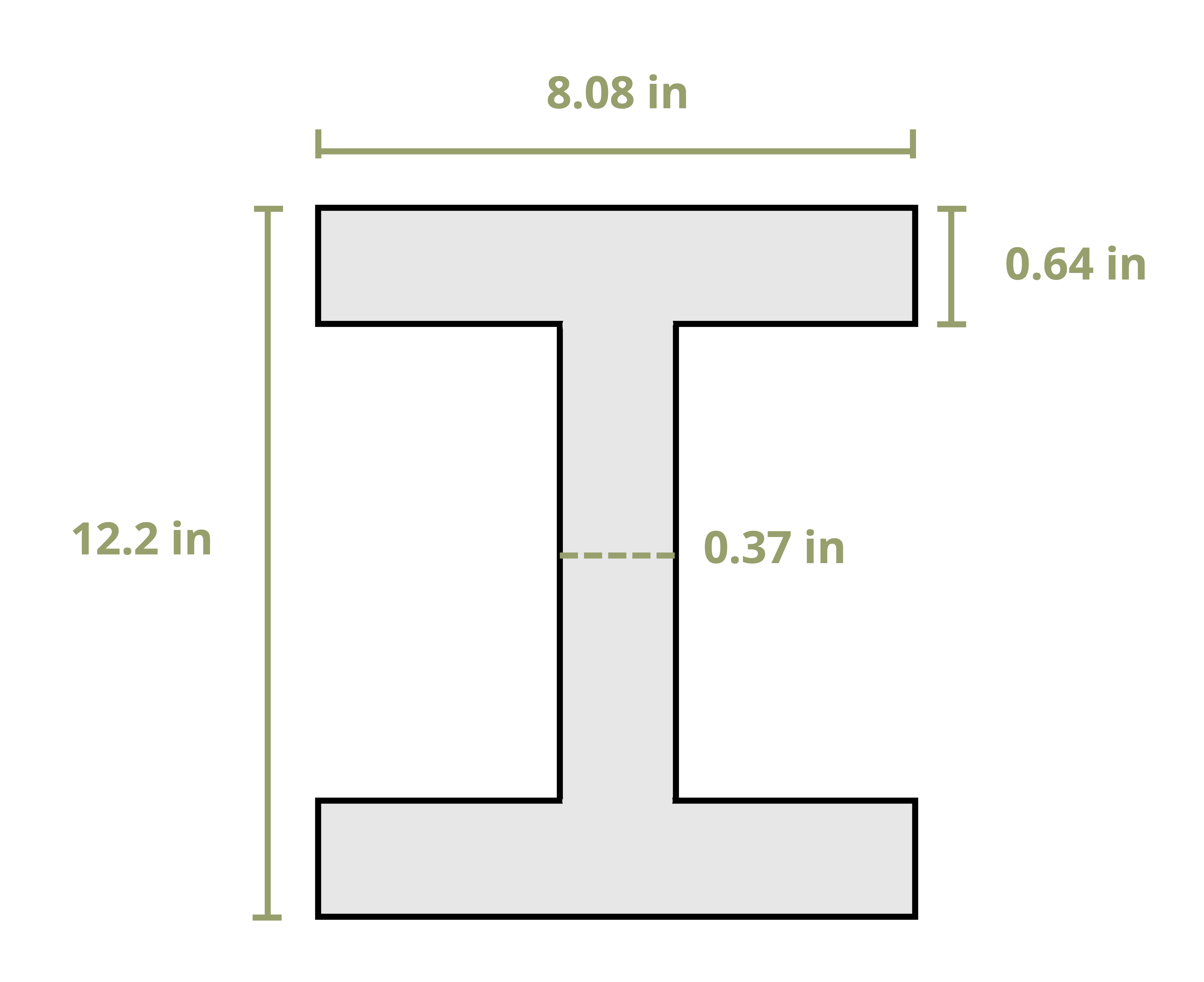

15.1.3 Bucking Direction

Columns that are pinned at both ends and have circular or square cross sections (where the moments of inertia are the same about any axis) could buckle in any direction. However, columns that do not have a symmetric cross-section will take place in the plane perpendicular to the principal axis of the minimum moment of inertia. For example, the ruler in Figure 15.2 has a rectangular cross-section. When a compressive force is applied to the ruler, it will buckle about the axis with the smaller moment of inertia. The axis of bucking might not be obvious for sections that are not symmetric. During buckling analysis, it’s essential to evaluate both directions to determine the axis with the lowest moment of inertia. Subsequently, this axis is utilized for computing the critical buckling load. Figure 15.6 illustrates column buckling of wood supports.

15.1.4 Critical Stress

We can use the Euler bucking equation to calculate the critical stress for a column by setting I=Ar2 where A is the cross-sectional area and r is the radius of gyration. For a more comprehensive discussion on the radious of gyration, see the Engineering Statics book by Baker and Haynes.

\[ \sigma_{c r}=\frac{P_{c r}}{A}=\frac{\pi^2 E\left(A r^2\right)}{A L^2} \]

Rearranging we have:

\[ \boxed{\sigma_{c r}=\frac{\pi^2 E}{\left(\frac{L}{r}\right)^2}} \tag{15.2}\]

σcr = critical stress on the column just before it buckles [Pa, psi]. Note that this stress must be less than that of the yield stress, or the column will fail due to yield stress before it buckles.

E = Elastic modulus of the material [Pa, psi]

L = Unsupported length of the column (pinned=pinned connection) [m, in.]

r = Smallest radius of gyration of the column [m, in.]

The quantity in the denominator, L/r, is called the slenderness ratio of the column. Many times columns are classified using the slenderness ratio as short, intermediate, and long. The smallest value of the radius of gyration is used to find the critical stress.

A plot of the critical stress versus the slenderness ratio is shown in Figure 15.7. For larger slenderness ratios the curve is hyperbolic. For smaller slenderness ratios, the critical stress is equal to the yield stress of the material. This graph illustrates that if the critical stress calculated using Euler’s equation is greater than the yield stress that is of no interest. The column will yield before it has the chance to buckle.

Example 15.1 demonstrates calculation of the critical buckling load and critical buckling stress.

15.2 Effect of Supports

Click to expand

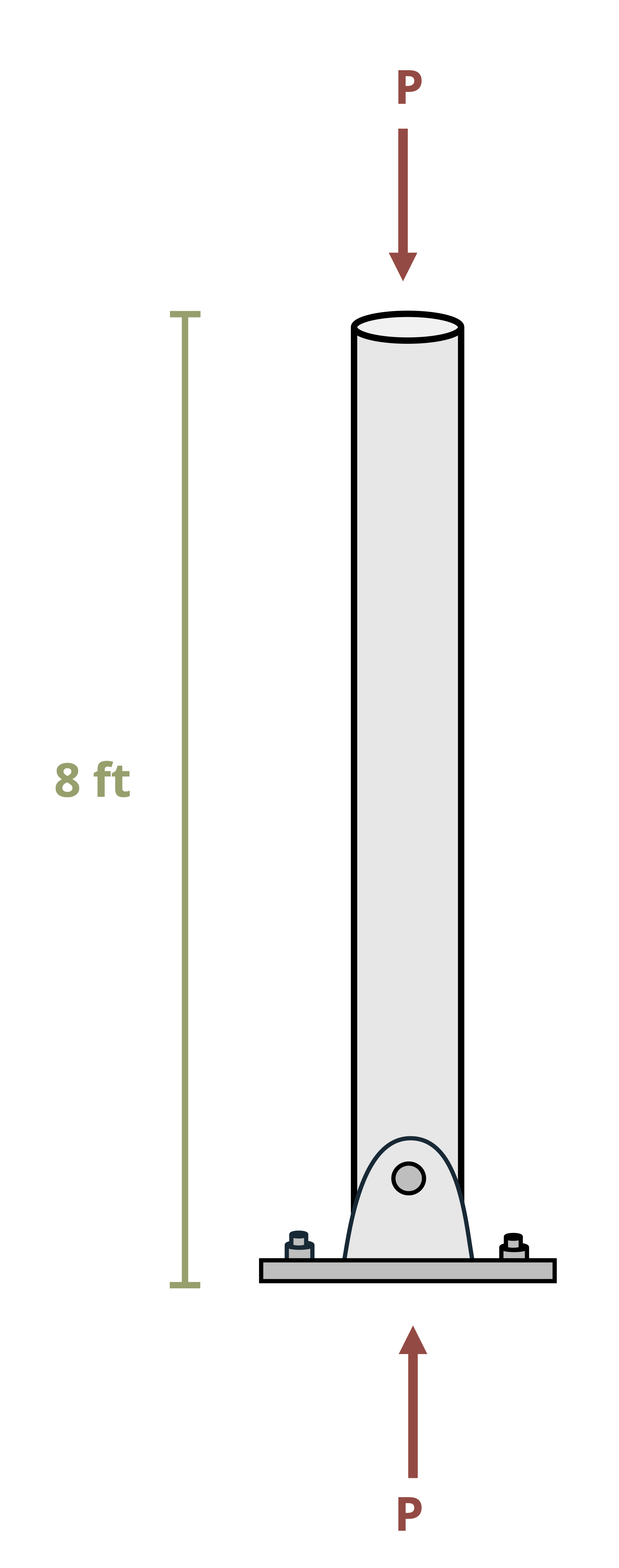

We derived Euler’s equation for bucking with pinned-pinned supports (the simplest case). However, in many cases, columns are supported by other end conditions. Just as we derived Euler’s formula for bucking by solving a differential equation for the pinned-pinned conditions, the same can be done for other types of support cases. We will derive one more here.

Let’s consider the case where a column is fixed at one end and free at the other end as shown in Figure 15.8 (A). Summing moments at the cut end of the free body diagram in Figure 15.8 (B) we get M=P(δ-y).

We can now write the differential equation using the elastic curve equation:

\[ \begin{aligned} & E I \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}=P(\delta-y) \\ & \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}+\left(\frac{P}{E I}\right) y=\left(\frac{P}{E I}\right) \delta \end{aligned} \]

Since the right side is not equal to zero, this equation is nonhomogeneous (note this differs from our earlier derivation for the pinned-pinned connection). There will be a particular and complementary solution.

\[ y=C_1 \sin \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I} x}\right)+C_2 \cos \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I} x}\right)+\delta \]

We can now employ boundary conditions to solve for the constants. At x = 0, y = 0, so C2 = δ. Also at x = 0, dy/dx=0, so C1=0. This leads us to the following deflection curve:

\[ y=\delta\left(1-\cos \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} x\right)\right) \]

At the free end of the column, x = L, we know that y = δ so:

\[ 0=\delta \cos \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I} L}\right) \]

The trivial solution δ = 0 shows that no matter what the P value no buckling will occur. So we have:

\[ \begin{aligned} & 0=\cos \left(\sqrt{\frac{P}{E I} L}\right) \\ & \sqrt{\frac{P}{E I}} L=\frac{n \pi}{2} \\ & \text{where n=1, 3, 5,...} \end{aligned} \]

The smallest critical load happens at n = 1, results in:

\[ P_{c r}=\frac{\pi^2 E I}{(2 L)^2} \]

Other support conditions can be derived in a similar manner.

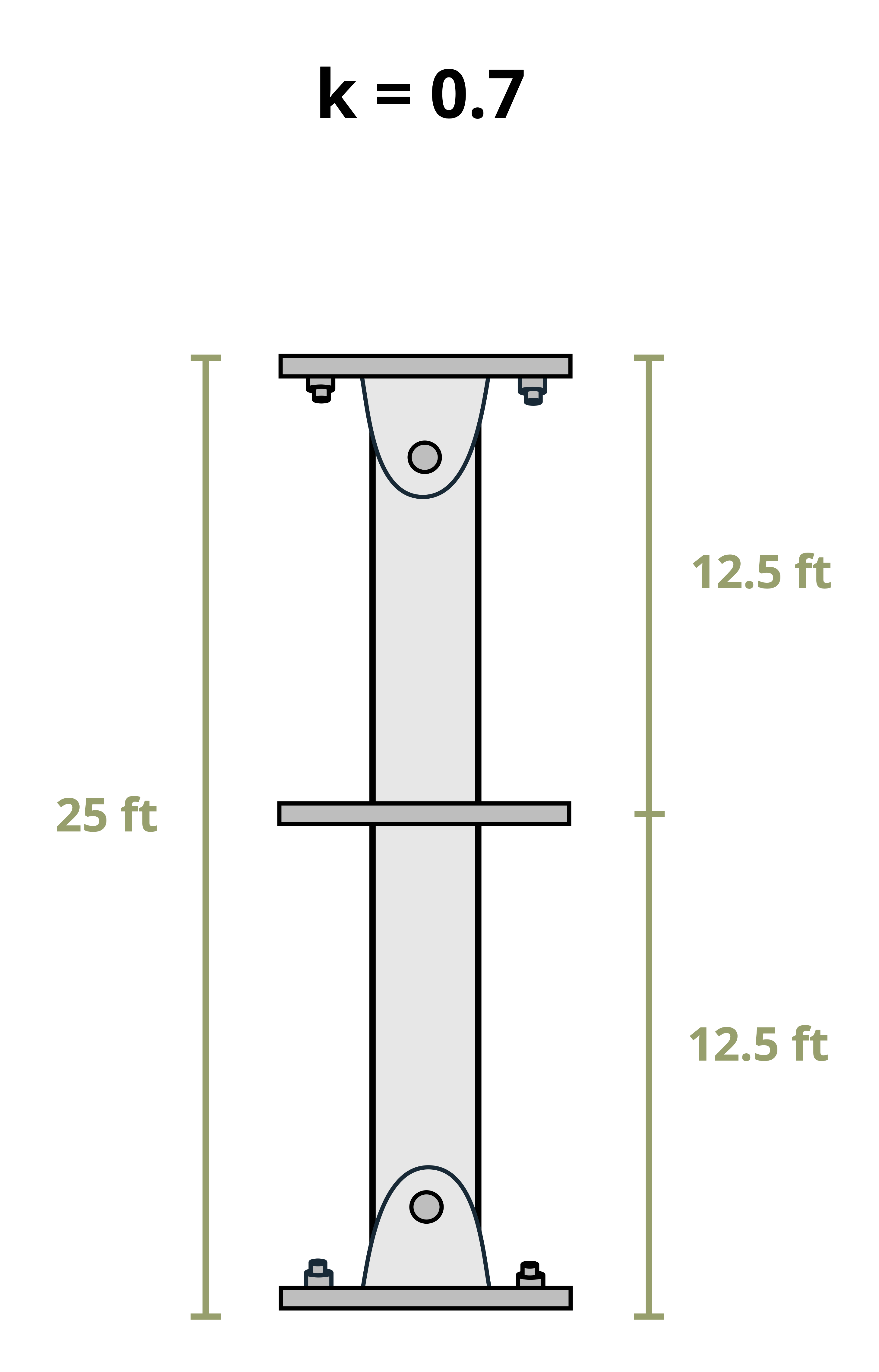

15.2.1 Effective Length

The critical load equation for the fixed-free column differs from the equation for the pinned-pinned column only by the length L being multiplied by a factor of 2. We will adjust the column length L to denote the distance between the points on the column where the moment is zero. This distance is referred to as the effective length, Le. For a pinned-pinned column, L = Le, as illustrated in Figure 15.9. As derived above, for a column with a fixed base and a free end, Le = 2L. Two other common end conditions are depicted in this figure relating L to Le. We can use one general equation for any support condition by replacing the effective length with KL, where K represents the effective length factor.

\[ \boxed{P_{c r}=\frac{\pi^2 E I}{(K L)^2}} \tag{15.3}\]

and

\[ \boxed{\sigma_{c r}=\frac{\pi^2 E}{\left(\frac{K L}{r}\right)^2}} \tag{15.4}\]

You can find the effective length factor, K, below each of the end conditions in Figure 15.9.

Example 15.2 and Example 15.3 demonstrate how to calculate the critical buckling load in columns with various different supports.